Subcapsular Liver Haematoma After Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy: A Rare Entity! « Contents

Louise Dunphy Frimley Health NHS Foundation Trust

Email: louise.dunphy1@nhs.net

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the gold standard treatment for symptomatic cholelithiasis. Complications can occur including haemorrhage, iatrogenic bile duct injury, gallbladder perforation, conversion to an open procedure and choledocholithiasis postoperatively. Subcapsular liver haematoma is a rare, life-threatening complication occurring after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Anatomical variations, pseudoaneurysms, the use of NSAIDs, haemangioma and iatrogenic liver damage have been suggested as possible risk factors. There is a paucity of cases reported. Depending on the time of onset of the patient’s symptoms, treatment can vary from expectant to surgical management. The authors present the case of a 79-year-old female presenting to the Emergency Department one day following a laparoscopic cholecystectomy with right upper quadrant abdominal pain and hypovolaemic shock. Further investigation with a CT confirmed the diagnosis of a subcapsular liver haematoma. She underwent right hepatic artery embolization. This paper will provide an overview of the aetiology, risk factors, clinical presentation, investigations and management of a subcapsular liver haematoma. It offers an important clinical reminder of maintaining a high index of clinical suspicion in patients presenting with acute onset abdominal pain and hypovolaemic shock following a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. A cystic duct stump leak due to improper clip placement, spontaneous clip displacement, ischaemic necrosis and elevated common bile duct pressures should also be considered in the differential diagnosis in patients presenting with hypovolaemic shock following cholecystectomy. An infected haematoma should also be considered in patients presenting to the Emergency Department a few weeks after surgery with abdominal pain and signs of sepsis.

Subcapsular liver haematoma, described as a blood collection under the Glisson capsule is a rare life-threatening occurrence after laparoscopic cholecystectomy, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography [ERCP] or colonoscopy. It can also occur in pregnancies complicated by HELLP Syndrome [haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelets] and pre-eclampsia. It is also associated with trauma, coagulopathies, hypoxia, maternal diseases and placental lesions. Patients typically present with right upper quadrant pain which may include signs of shock if the bleeding is severe. A high index of clinical suspicion is requiring to render the diagnosis to prevent morbidity and mortality.

Presentation

79-year-old female presented to the Emergency Department, with acute onset of right upper quadrant abdominal and epigastric pain. Her medical history included hypertension, GORD, hypothyroidism, chronic renal impairment and hypercholesterolaemia. Her medications included levothyroxine 50mcgs od, lansoprazole 30mg gastro-resistant tablets, pyridoxine 50 mgs od and bendroflumethiazide 10 mgs od. Further investigation with an ultrasound scan of her abdomen showed a thin-walled gallbladder with several mobile gallstones. She underwent an elective day case laparoscopic cholecystectomy, Hem-o-lok clips were used and haemostasis was achieved. Histopathology showed features of chronic cholecystitis with cholelithiasis. One day post-surgery, she presented to the Emergency Department with acute onset confusion, abdominal pain and distension. She was hypotensive [BP 70/50mmHg] and tachycardic [heart rate 110 bpm]. On examination, guarding was elicited in the right upper quadrant.

Investigations

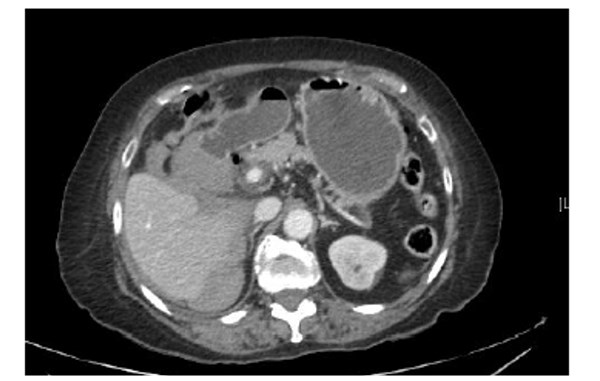

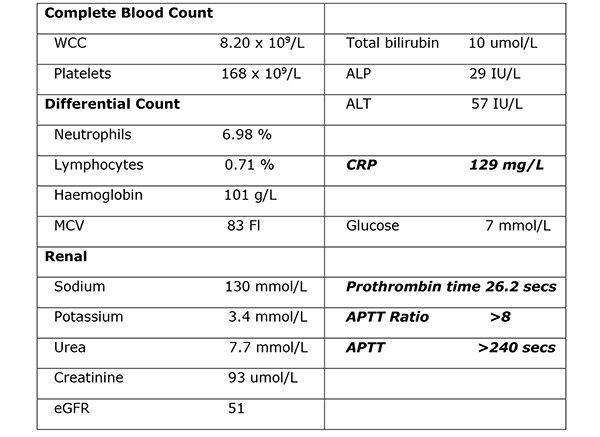

Her venous blood gas confirmed a raised lactate of 4.3mmol/l and a haemoglobin of 104g/l. Haematological investigations confirmed a raised CRP of 129mg/L, Table 1. Her chest radiograph showed atelectasis at the left base with no evidence of sub-diaphragmatic free air. Her urine dip was negative. She commenced treatment with intravenous anti-microbial therapy [amoxicillin, metronidazole, gentamicin] for suspected intra-abdominal sepsis. Further investigation with a CT abdomen and pelvis showed a large haematoma in the gallbladder bed extending down to the right paracolic gutter (Figure 1). There was a linear streak of high attenuation within the porta hepatis at the site of the cystic artery. The appearances were suggestive of a leaking cystic artery stump, although the hepatic artery itself was not clearly visualised. A small volume of fluid was noted in the pelvis. Her clotting was deranged and she received 10mgs of vitamin K IV, tranexamic acid 1g IV and three units of FFP.

Figure 1. Further investigation with a CT abdomen and pelvis showed a large haematoma in the gallbladder bed

extending down to the right paracolic gutter.

Table 1. Haematological investigations confirmed a raised CRP of 129mg/L.

Differential diagnosis

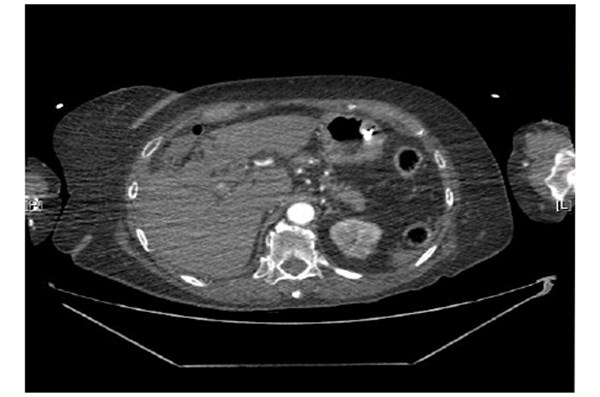

The clinical impression was of a cystic duct stump leak due to improper clip placement, clip displacement or a subcapsular liver haematoma. Further investigation with a pre-contrast CT was recommended to determine an active bleed as the clips made interpretation difficult. Pre contrast, arterial phase and delayed phase images of her abdomen and pelvis were performed. A large subcapsular collection extending along the medial inferior border of the liver, apparently extending from the gallbladder fossa was noted. Arterial phase images showed the hepatic artery lying close to and abutting the two blushes of contrast again raising the suspicion of active focal bleeding (Figure 2). Note was also made of a variation of the coeliac axis. Two main branches were the left gastric and hepatic artery. The splenic artery appeared to arise off the left gastric artery. There was a tiny accessory vessel just arising after the origin of the coeliac axis. This extended towards the right adrenal gland. Subphrenic fluid represented subcapsular haemorrhage. Two small blushes of contrast were demonstrated suspicious for contrast extravasation from an active bleeding point. A repeat blood gas confirmed a drop in her haemoglobin to 71 g/l. She was transfused two units of packed red blood cells. She was transferred to the Intensive Care Unit for further observation. She required an infusion of metaraminol to maintain her blood pressure. She was self-ventilating and no respiratory support was required. Her haemoglobin remained stable and no further transfusions were required.

Figure 2. Arterial phase images showed the hepatic artery lying close to and abutting the two blushes

of contrast again raising the suspicion of active focal bleeding.

Treatment

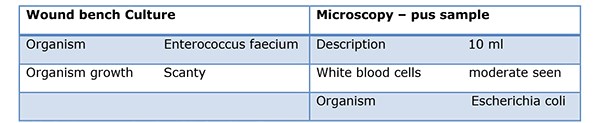

As her intermittent haemorrhage persisted, prophylactic embolization was performed. Under fluoroscopic guidance, a right renal, coeliac and selective hepatic angiogram was performed. The right hepatic artery was embolised with 710-1000 micro polyvinyl alcohol particles until stasis was achieved distal to the point of origin of the gastroduodenal artery. Despite antimicrobial therapy her high inflammatory markers persisted [WCC 17x109/L and CRP 342mg/L]. A CT Abdomen/pelvis with contrast was performed. Compared to her previous CT, an evolving right hepatic large haematoma was observed. Her anti-microbial therapy was changed to ertapenem. Under US guidance, the right hepatic complex collection was punctured using a 19G needle to obtain dark red fluid, a sample of which was sent for MC&S. In view of her sepsis, a 12F drain was inserted and placed on free external drainage. Her pus cultured Escherichia coli, Table 2.

Table 2. His pus sample cultured Escherichia coli.

Outcomes

As her inflammatory markers improved, her anti-microbial therapy was down-stepped to levofloxacin and metronidazole. She developed hypoactive delirium, hyperkalaemia [6.5mmol/L], hyponatraemia [124 mmol/l], hypomagnesemia [0.65 mmol/L] and hypophosphatemia [0.68mmol/l] resulting in a prolonged hospital stay. She was reviewed by the dietician and commenced total parenteral nutrition to maintain her calorie intake. Her electrolyte imbalance was caused by her dehydration and thiazide diuretics. She commenced treatment with melatonin modified release tablets 2mg od. Further investigation with a CT Head showed generalised involutional change predominantly affecting the temporal lobes. Her drain was removed after three weeks and an interval CT of her abdomen and pelvis two months later showed a significant reduction in the size of her haematoma. She was discharged home uneventfully after one month.

Discussion

Approximately 12-15% of the UK adult population have gallstones, with up to 4% becoming symptomatic every year. [1] More than 45,000 cholecystectomies are performed annually in the UK. Since the advent of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the 1990s, it has become the gold standard for the management of symptomatic cholelithiasis. Large cohort studies have reported complication rates of 2-6% following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. [2] These complications include haemorrhage, gallbladder perforation, common bile duct injuries and conversion to an open procedure. Other risks include a subhepatic abscess, iatrogenic bile duct injury and choledocholithiasis postoperatively. [3] Bleeding occurs in <1%. [2] The anatomical sites most commonly affected include the gallbladder bed after its removal, sites of introduction of trocars, the cystic artery, falciform ligament and haemorrhage from a ruptured liver capsule. [2] In the open cholecystectomy era, cystic duct stump leaks were rarely reported. In the era of LC, improper clip placement, spontaneous clip displacement, ischaemic necrosis and elevated common bile duct pressures have been implicated as the cause, occurring in 0.12% of cases. Cystic duct stump leaks can be prevented by a high index of suspicion for postoperative complications and by prompt and appropriate intervention.

A subcapsular liver haematoma, described as a blood collection under the Glisson capsule is an extremely rare, life-threatening complication after laparoscopic cholecystectomy, with only a few cases reported in the literature. [4] Spontaneous haemorrhage of liver parenchyma following normal manipulation of the gallbladder and liver intraoperatively has also been described. This traction may be adequate to cause haemorrhage of a vulnerable haemangioma or surrounding liver parenchyma. It may occur early [up to 24 hours after surgery], presenting with acute onset upper right quadrant pain and hypovolaemic shock if the liver capsule has ruptured. Peritonism may be elicited on physical examination. It can also occur several weeks after the operation presenting with non-specific abdominal pain and a fluid collection on USS. An infected haematoma may present with pyrexia, abdominal pain and sepsis. Bacterial translocation from the gut is thought to be the cause of this superimposed infection. [5] It also occurs in <2% of pregnancies complicated by HELLP Syndrome [haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelets] and pre-eclampsia. It is also associated with trauma from a difficult labour or a breech presentation, hypoxia, coagulopathies, maternal diseases and placental lesions. In a neonate, it may present with poor feeding, listlessness, pallor, jaundice, tachypnoea and tachycardia. Other causes may include amyloidosis, rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma, adenoma, focal nodular hyperplasia or a haemorrhagic cyst. It is also a rare complication after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography [ERCP] with a paucity of cases in the literature. Iatrogenic puncture of a peripheral intrahepatic biliary tree resulting in laceration of small parenchymal vessels by an endoscopic guide wire may explain this phenomenon. [6] Acute onset of abdominal pain associated with hypotension and tachycardia after ERCP should raise the clinical suspicion of intrahepatic bleeding with Glisson’s capsule distension. Acute fascioliasis, a food-borne transmitted zoonosis caused by the liver trematode F. hepatica can manifest with a subcapsular liver haematoma, resulting from destruction of blood vessels during the intra hepatic migration of the immature parasites. Other risk factors for its development include the use of diclofenac, aspirin and ketorolac, a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory injection used for perioperative pain management. [7] Intra-operatively, the capsule of the liver can be damaged when dissecting off the gallbladder. Liver traction should be minimized through careful trocar placement while still allowing a critical view of safety to prevent visceral injury. A hepatic haemangioma has also been suggested as an aetiological risk factor. Anatomical variations involving the hepatic vascular system occurring in 12% of individuals, may result in slow bleeding post operatively. [8] Furthermore, the presence of a pseudoaneurysm is considered a risk factor. They have also been described after a liver biopsy, trauma to the abdomen and following the oral contraceptive pill. [9] CT is the investigation of choice for evaluating liver trauma as it has a high sensitivity [95%] and specificity [99%] for detecting liver injuries. [10] Abdominal ultrasound can also help to delineate the lesion, rule out a rupture and aid in serial follow up.

Displacement of a surgical clip from the cystic duct stump should also be considered in the differential diagnosis in patients presenting with haemorrhagic shock following a cholecystectomy. It has become common practice to place at least 2 clips on the proximal side of the cystic duct [CD] for insurance. Despite this practice, there are numerous reports of laparotomies in which a clipless CD has been identified as the cause of a patient’s bile peritonitis. [11][12] Necrosis of the CD stump proximal to the applied clips has also been reported as a cause of a cystic duct stump leak. Ischaemic necrosis caused by devascularization of the CD has also been implicated. [13] It has also been hypothesized that retained common bile duct stones can lead to excess pressure in the biliary tree leading to either perforation of the CD or displacement of the surgical clips. The average time to detection of a CDSL is 3-4 days post operatively. Individuals present with right upper quadrant abdominal pain [80%], nausea or vomiting [35%] and pyrexia [30%]. A leucocytosis is described in 70%. [14] The most successful imaging modality for correctly diagnosing CDSLs is ERCP, followed by MRCP. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography is also the primary treatment modality in most postoperative biliary leaks, diminishing delay in therapy once the diagnosis has been confirmed. If a CDSL is found, a sphincterotomy should be performed and a stent placed, with care taken to evaluate for retained CBD stones. Radiologically guided drainage of the biloma has also been used in treating CDSLs. Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage has been demonstrated to be effective in CDSLs in small series. [15] The majority of cystic duct stump leaks heal spontaneously when bile is shunted past the defect. Percutaneous or endoscopic coil embolization, fibrin glue, and gelatin sponge injection are alternative approaches for refractory cases. Immediate development of a subscapular haematoma is a potentially life-threatening event due to hypovolaemic shock. Urgent evacuation of the haematoma using percutaneous drainage under ultra-sound guidance may be required. A relaparotomy or re-laparoscopy is required in haemodynamically unstable patients. In cases of a small haematoma in a stable patient, conservative management is appropriate. Treatment with broad spectrum antibiotics is initiated in cases of an infected haematoma. Although subcapsular haematoma is a very rare occurrence following a laparoscopic cholecystectomy it should be considered in the differential diagnosis in patients presenting with abdominal pain and signs of shock. A prompt diagnosis is required to prevent morbidity and mortality.

References

- Gill MS et al. Cholecystectomy audit: waiting time, readmissions and complications. Gut, 2015, 64 [S1], A402.

- De Castro SM, Reekers JA, Dwars BJ. Delayed intrahepatic subcapsular haematoma after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Clin Imaging, 2012, 36: 629-31.

- Duca S, Bala O, Al-Hajjar N, Lancu C, Puia JC, Munteanu D et al. Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy: incidents and complications. A retrospective analysis of 9542 consecutive laparoscopic operations.

- Liu QF, Bian LL, Sun MQ, Zhang RH, Wang WB, Li YN et al. A rare intrahepatic subcapsular haematoma: a case report and literature review. BMC Surgery, 2019, 19:3.

- Shea JA, Healey MJ, Berlin JA et al. Mortality and complications associated with laparoscopic cholecystectomy. A meta-analysis. Ann Surg 1996, 224:609-20.

- Orellana F, Irarrazaval J, Galindo J, Balbontin P, Manríquez L, Plass R et al. Subcapsular hepatic hematoma post ERCP: a rare or an underdiagnosed complication? Endoscopy, 2012;44, Suppl. 2.

- Vuilleumier H, Halkic N. Ruptured subcapsular haematoma after laparoscopic cholecystectomy attributed to ketorolac-induced coagulopathy. Surg Endosc 2003,17; 659.

- Duric B, Ignjatovic D, Zivanoic V. New aspects in laparoscopic cystic artery anatomy. Acta Chir Iugosl, 2000: 47: 105-7.

- Davis TJ, Berk RN. Benign hepatic lesions in women taking oral contraceptives. Gastrointst, Radiol, 1977, 2, 213-219.

- Ahmed N, Vernick JJ. Management of liver trauma in adults. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2011;4 [1]: 114-9.

- Hanazaki K, Igarashi J, Sodeyama H, Matsuda Y. Bile leakage resulting from clip displacement of the cystic duct stump: a potential pitfall of laparoscopic cholecystectomy.Surg Endosc. 1999;13(2):168-171.

- Li JH, Liu HT. Diagnosis and management of cystic duct leakage after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: report of 3 cases. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2005; 4(1):147-151.

- Journe´ S, De Simone P, Laureys M, Le Moine O, Gelin M, Closset J. Right hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm and cystic duct leak after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2004;18(3):554-556.

- Wise Unger S, Glick GL, Landeros M. Cystic duct leak after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a multi-institutional study. Surg Endosc. 1996;10(12):1189-1193.

- Cozzi G, Severini A, Civelli E, et al. Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage in the management of postsurgical biliary leaks in patients with nondilated intrahepatic bile ducts.Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2006;29(3):380-388

Cite this article as https://daysurgeryuk.net/en/resources/journal-of-one-day-surgery/?u=/2019-journal/jods-294-november-2019/subcapsular-liver-haematoma-after-laparoscopic-cholecystectomy-a-rare-entity