Introduction of Day Case Pathway for Total Hip Arthroplasty « Contents

Mr Michael Kent MBBS, BSc, MSc (Tr Surg), FRCS (Tr&Orth), Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon 1

Dr Claire Blandford MBBS FRCA EDRA PGCertMedEd, Consultant Anaesthetist 1

Dr Anne-Marie Bougeard MA (Oxon), MBBS, MRCP, FRCA, Specialty Trainee 7, Anaesthesia 2

Dr Mary Stocker MA (Oxon), MBChB, FRCA, Consultant Anaesthetist 1

Contributors

Mrs. Bernice Sullivan, Senior Physiotherapist 1

Mrs. Alex Alen, Senior Day Surgery Nurse 1

Mrs. Jo Allen, Outreach Team Leader 1

Authors' addresses

- Torbay and South Devon NHS Foundation Trust, Lowes Bridge, Torquay, Devon, TQ2 7AA, UK

- University Hospitals Plymouth NHS Trust, Derriford Road, Plymouth, Devon, PL6 8DH, UK

Key words Ambulatory surgery, Day Case Hip Replacement, Day Case Arthroplasty

Abstract

Introduction Outpatient total hip arthroplasty (THA) is commonplace in the United States (US) offering advantages for patients and healthcare providers. We hypothesised that it would be possible to perform day case THA in the NHS. There are limited reports of this in the United Kingdom (UK).

Method We report our experience of implementing a pathway to allow safe day of surgery discharge following THA. Data were prospectively collected on 32 patients between September 2018 and January 2020.

Results 30 patients (94%) were discharged home on the same day. Dizziness and postural hypotension associated with deviation from our anaesthetic and analgesia protocol were the only reasons for the 2 failed discharges. The median time to discharge was 9hrs 34mins (interquartile range 9hrs 19mins – 11hrs 31mins [total range 8hrs 30mins – 12hrs 2mins]). Both unplanned admissions were discharged the day after surgery. Post discharge data was available in all patients: 22 (74%) reported no or mild pain; 8 (26%) reported moderate pain. There were no readmissions. All patients had high levels of satisfaction. 4 patients had staged consecutive day case THAs. ‘Second side’ patients much preferred the day case pathway compared with previous inpatient stays.

Conclusion We found that patients can be safely discharged on the day of surgery after THA, with high levels of satisfaction. We had a very low failed discharge rate (6%) compared with the published literature. Expectation management, patient education, consistent messaging and highly protocolised treatments were vital factors. This clearly offers improved management of resources and financial savings to healthcare trusts.

Introduction

Most NHS hospitals in the UK face daily challenges to inpatient capacity, placing significant pressure on elective surgery waiting lists resulting in ever increasing delays for patients awaiting surgery. Lower limb arthroplasty is particularly vulnerable to cancellation, as priority is given to urgent and cancer surgery when there are capacity pressures. In the winter of 2017-18 a temporary amnesty was placed on elective orthopaedic operating by NHS England in order to free up beds for non-elective admissions [1].

Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocols are well established in orthopaedic practice in the UK [2-4]. They are designed to attenuate the surgical stress response, allow patients earlier return to normal function and reduce complication rates [5]. Units with strong adherence to ERAS principles have lower lengths of stay and readmissions and are able to provide high quality treatment with a lower demand on precious inpatient resources [2,4].

In the US and Scandinavia, lower limb arthroplasty surgery with discharge on the day of surgery is a well-established, safe practice [6-12]. In 2011, our hospital commenced a day case pathway for unicondylar knee arthroplasty (UKA), and 70% of our patients now undergo this operation as a day case [13,14]. This is popular among patients, offering excellent clinical outcomes, and low complications and readmissions.

Our unit has a well established ERAS model which includes: standardised preassessment and optimisation of existing co-morbidities, an extensive preoperative patient education programme (including comprehensive booklets, videos and ‘Joint School’ group sessions run by surgeons, physiotherapists and nurses) and a well-established orthopaedic outreach team who provide post-discharge care for all arthroplasty patients in their homes after surgery.

We hypothesised that it would be possible to replicate the success of our UKA practice and undertake total hip arthroplasty (THA) with discharge home on the day of surgery, and designed a pilot study protocol to assess safety and feasibility [13-15]. There are limited reports of outpatient THA in the United Kingdom. We present our experience of implementing this pathway in a medium sized district general hospital.

Patients and Methods

Background work

Using quality improvement methodology, treatment interventions within the first 24hours of the inpatient pathway were assessed: time to mobilisation, frequency of urinary catheterisation, incidence of significant postoperative nausea and vomiting, and requirements for rescue analgesia.

Similarly, anaesthetic/analgesic techniques, physiotherapy protocols and follow up arrangements with the outreach team were assessed and refined to create a robust pathway for day case THA patients.

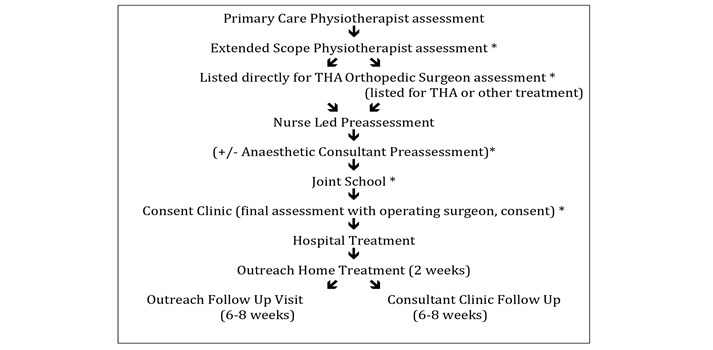

Additionally, we established points in the referral pathway (from primary care referral to consultant outpatient clinic assessment), where suitable patients could be identified and consideration was given to how patients could be appropriately counselled and recruited to consider a day case THA (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Patient treatment pathway * opportunities to discuss day case surgery with patient.

Patient selection

Patients with symptomatically intrusive hip pathology, who had failed conservative treatment, requiring a THA, were considered.

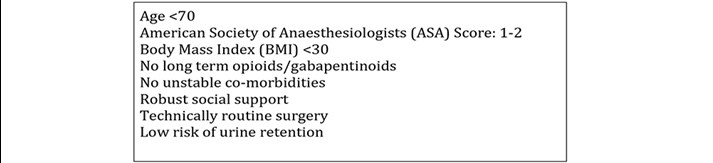

We identified criteria for patient selection for the pilot study, selecting conservative criteria for the initial phase (Figure 2). As our experience developed, we began to relax some of these criteria to include some ASA3 patients and one, very motivated patient who was pre-operatively taking opioid & gabapentinoid medication.

Figure 2. Inclusion criteria.

In accordance with national day surgery guidance [16] we ensured that all patients on this pathway were booked as intended day cases. This is essential for three reasons:

- National reporting for day surgery relies on the documented intended management as a day case and a length of stay of zero days.

- Setting patient expectations is key to the success of day surgery pathways. If the patient is booked as a day case they will receive consistent messaging from all members of the multidisciplinary team (MDT). More importantly the patient and their carer are clear about their intended pathway and can prepare appropriately for same day discharge.

- In times of hospital escalation when bed capacity is limited, patients who are scheduled for inpatient surgery have a much higher risk of cancellation (even if they may in fact have been able to be discharged as day cases). Ensuring that patients are scheduled as day cases, not requiring of any inpatient resource, decreases their risk of cancellation.

Anaesthetic technique

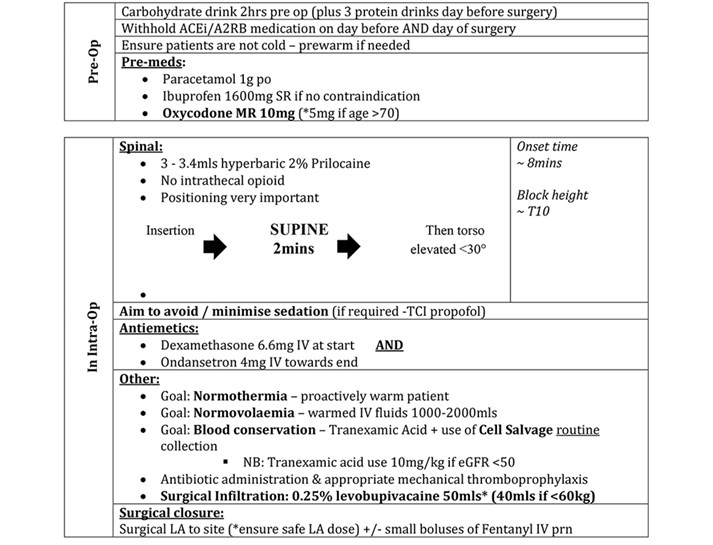

We analysed our previous year’s postoperative pain scores and correlated these with the anaesthetic technique used. In addition, we reviewed published ambulatory protocols [6-9,17,18] to design our anaesthetic technique as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Anaesthetic/perioperative protocol.

Surgical technique

Between September 2018 and January 2020, 32 patients were selected to have their THA as a day case. All patients received a standard THA, performed by or under the direct supervision of five consultant hip arthroplasty surgeons (MK, MA, GH, SP, AA), Several different THA implant systems were used: Exeter cemented stems, Trident acetabular systems (Stryker, Mahwah, New Jersey), Corail uncemented stems and Pinnacle uncemented acetabular systems (DePuy Synthes, Warsaw, Indiana). It is important to emphasise that there was no deviation from the surgeon’s standard approach or technique.

After implantation of the femoral components, all patients received infiltration of 40-50mls 0.25% Levobupivacaine local anaesthetic into the surgical field (joint capsule, muscle, fascia lata, subcutaneous tissues and skin) using a 22 gauge needle. Routine cell salvage collection was performed whenever possible with blood being processed and re-transfused if sufficient volumes were obtained. This strategy was introduced as a cost neutral intervention in place of routinely performing a second group and save sample on the day of surgery. Our trust was an early adopter of cell salvage so we were fortunate to have sufficient processing machines available to introduce this change. Processing was performed if there was deemed to be sufficient volume required for the device (minimum 55mls concentrated red cell volume), this threshold was reached in 65% of our cohorts’ patients.

No surgical drains were used. Transosseous muscle repair was undertaken in all cases using drill holes and Ethibond sutures. Multi-layered surgical closure was undertaken with deep absorbable Vicryl sutures, subcutaneous absorbable Monocryl sutures and additional surgical clips in selected cases. Wound glue and an adherent water-resistant dressing were applied in all cases.

Our hospital has a stand-alone dedicated day surgery unit (DSU) connected to the main hospital site via an internal corridor. The majority of day surgery is undertaken within this unit, which is staffed by a dedicated day surgery team. However, there are no laminar flow theatres within DSU so these THAs were performed in the main orthopaedic theatres. Where possible, all cases were planned as the first morning case on the operating list. Post-operatively, patients spent a short time in primary recovery before being transferred to the DSU for secondary recovery and discharge. A small number of patients underwent surgery at the weekend when the DSU was closed. These patients were managed postoperatively on the inpatient orthopaedic ward.

Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis

All patients received mechanical prophylaxis whilst in hospital and a prophylactic dose of 5000iU of Dalteparin 6 hours after administration of their spinal anaesthetic. Patients who were not on oral anticoagulation then received 150mg of Aspirin once a day for 28 days. Patients on anticoagulation restarted this on the day after surgery and where required, dose monitoring was undertaken by the outreach team.

Mobilisation and discharge process

All non-diabetic patients were given an energy drink in their initial recovery stage (Fresubin energy 200mls or similar), with an aim to reduce any first mobilisation dizziness and enhance feelings of wellbeing. They were then encouraged to eat and drink as normal and were given regular analgesia with additional top ups as required (see analgesia section). As soon as the spinal anaesthetic had worn off and they felt able to do so, patients were mobilised by physiotherapists, full weight bearing with crutches, applying no hip precautions.

Standard discharge criteria included: transfer from supine to a standing position; walk >30 metres without assistance and ascend and descend a flight of stairs. They were given an information booklet and enrolled in routine outpatient physiotherapy. All patients had a radiograph undertaken prior to discharge, which was reviewed by the operating surgeon.

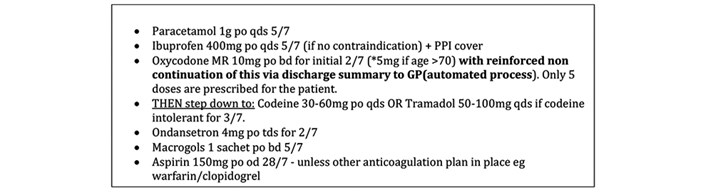

On discharge, patients were provided with a standardised medication package and checklist with timings, drug descriptions and instructions (Figure 4). Pain and nausea scores were recorded at the point of discharge. Patients were given a 24-hour emergency contact number for the day surgery nursing team during working hours or a senior orthopaedic nurse out of hours.

Figure 4 Discharge medication.

All patients were visited at home on the morning after surgery by the orthopaedic outreach team where symptoms and progress were assessed, observations and blood tests were taken, and medication advice was given. Had urethral catheterisation been required then outreach managed the removal process.

The outreach team visited the patients at home again on days 3, 7, 10, providing wound care and support. Any issues were fed back directly to the operating surgeon. It is important to note that whilst the outreach team provided vital support to our day case pathway, this is a longstanding established role for all arthroplasty patients, not a new service implemented for this pilot.

Additionally, all patients were telephoned at 24 hours by the DSU team to record pain scores, nausea or vomiting, dizziness, drowsiness and at 7 days satisfaction with the process was recorded. Pain levels were assessed using a Verbal Rating Scale, satisfaction using a simple descriptive scoring system.

Patients were reviewed at six weeks post operatively by the operating surgeon.

Results

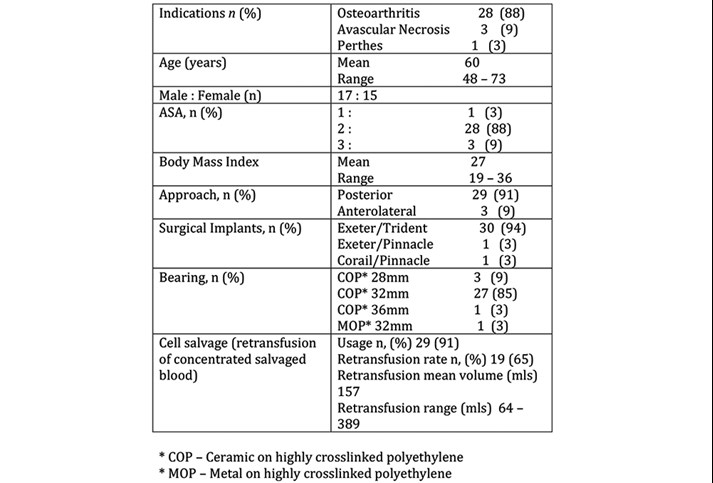

Table 1 shows the indications for surgery, patient demographics, implant and cell saver usage. Most patients received a hybrid THA with a 32mm ceramic on highly crosslinked polyethylene bearing via a posterior approach. The majority of patients were ASA-2, with a mean age of 60 years and a BMI of 27. 65% of patients received an autotransfusion, with a mean re-transfused volume of 157mls.

Table 1 Patient demographics/Intraoperative data.

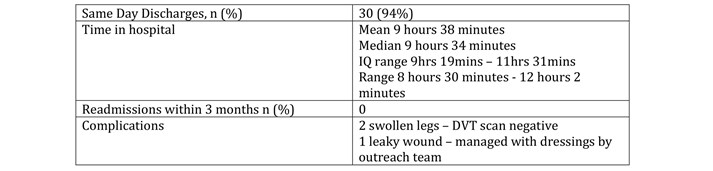

Table 2 shows that of the 32 planned day case THA patients, 30 (94%) were successfully discharged on the day of surgery. No patients were readmitted within a three-month period. There were no significant complications (dislocations/infections/VTE). Two patients had moderately swollen operative limbs but had negative DVT scans. One patient had a leaky wound 10 days postoperatively, that was managed successfully with dressings by the outreach team.

Table 2 Discharge/Complication data.

The two patients (6%) who could not be discharged both had significant dizziness due to postural hypotension which precluded them completing physiotherapy discharge goals on the day of surgery. For these patients, Day 0 pain scores were 1/10 and 2/10 and they reported no nausea. Both were successfully discharged on the morning after surgery and had undergone a posterior approach THA. Of interest, in both of these cases there was deviation from the protocol. Due to timing concerns the patients had received a 0.5% levobupivaciane spinal, which is longer acting than Prilocaine both in terms of motor block and haemodynamic effect. Other deviations included failure to appropriately omit pre operative ACE inhibitor medication (1), non administration of post operative energy drink (1) and non standard timing of analgesia(1). There was one patient where deviation from protocol did not result in failed discharge however, where the protocol was followed, 29/29 patients successfully discharged on their day of surgery.

25 patients (78%) were discharged through the DSU. Seven patients (22%) were managed through the inpatient orthopaedic ward (due to the fact that the DSU was not open at the weekend). Both unplanned admissions were initially managed through the DSU and admitted overnight to the inpatient ward.

31 patients (97%) were operated on as the first case of the morning session. One patient was operated on later in the day (with a start time of 1215) but was successfully discharged on the day of surgery, from the inpatient ward.

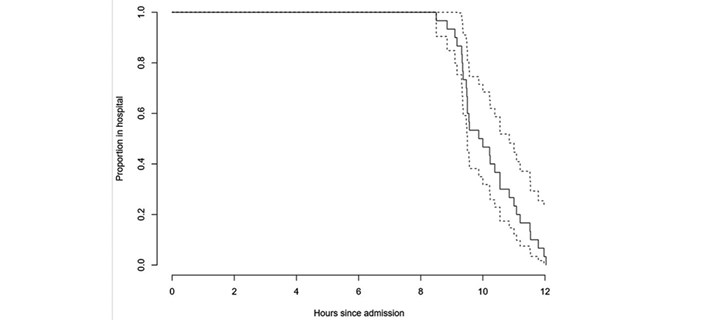

Seven patients were ‘second sides’ having had a previous THA through an inpatient pathway. Six of these patients were discharged on the day of surgery. Four patients had staged consecutive THAs done as a day case and were all successfully discharged on the day of surgery. The median time to discharge was 9hrs 34mins (interquartile range 9hrs 19mins – 11hrs 31mins [total range 8hrs 30mins – 12hrs 2mins]). Time to discharge is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5 Patient demographics/Intraoperative data.

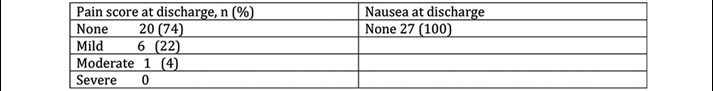

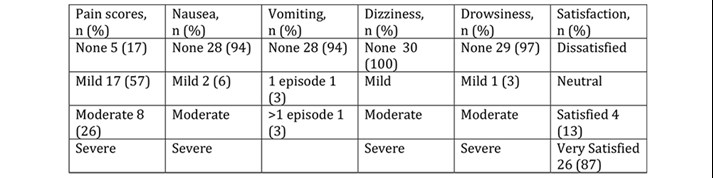

Discharge pain and nausea scores were collected for 27/30 patients discharged on the day. Table 3 shows that 96% of patients had no or mild pain and no patients had nausea at the point of discharge. Table 4 shows that at 24 hours, 74% of patients had no or mild pain, 26% moderate and no patient reported severe pain. There were very low levels of day 1 nausea and vomiting (94% of patients reported no symptoms). No patients reported dizziness and drowsiness was very rare (3%). All patients were either very satisfied (87%) or satisfied (13%) with day case THA, no patient reported dissatisfaction with this process.

Table 3 Anaesthetic/perioperative protocol.

Table 4 Outcome scores at 24 hours, satisfaction at 7 days.

There was no difference in time to discharge on the day of surgery or pain scores at discharge comparing posterior approach patients and anterlolateral approach patients. All three anterolateral approach patients reported ‘moderate’ pain at 24hours, whereas 80% of posterior approach patients reported ‘no’ or ‘mild’ pain at 24 hours. In our cohort, ASA grade did not appear to be an independent factor in determining successful day case discharge, indeed our three ASA3 patients were successful day cases, as were the two technically complex cases.

One patient had an asymptomatic postoperative haemoglobin of 90g/dl. She was the only patient with a postoperative level of less than 100g/dl. There were no other abnormalities comparing postoperative blood tests with baseline.

Discussion

This pilot study has demonstrated that day case THA in the NHS is feasible, safe and acceptable to patients.

We have achieved a 94% successful discharge rate with no readmissions or complications. Our unplanned admission rate of 6% is extremely low and compares very favourably with rates of up to 60% reported by some units [6, 10, 11]. Indeed, all four patients who required a further THA following a successful previous day case THA opted to follow the day case pathway again for their second side. Similarly, all seven of the patients who had undergone a previous inpatient THA stated that they far preferred the day case pathway, as it offered an equivalent or better standard of care in the comfort of their own home, with accelerated rehabilitation and recovery.

The success of this pilot to date is multifactorial. It is well documented that units with strong adherence to protocolised ERAS pathways are more likely to achieve consistent outcomes [2-4, 9-11]. Our hospital is in a strong position to be able to provide day case pathways for lower limb arthroplasty. We have a well established, successful day surgery unit co-located on site, extensive experience of undertaking major orthopaedic and general surgery as a day case, a robust enhanced recovery programme and a specialist orthopaedic outreach team to visit patients postoperatively in their own home.

In our opinion, patient selection, engagement with the day case pathway and achieving consistent messaging from staff are key determinants of a successful outcome. We believe that introducing the concept of day case early in the patient’s referral pathway is vital to set expectations and ensure confidence in the pathway through education. Patients who are medically and socially suitable for a day case procedure are then primed to expect to mobilise early and return home on the day of surgery.

Adherence to ERAS principles is vital to success [4]. Physiologically, patients should be optimised prior to surgery, undergo anaemia management, and have perioperative warming to normothermia. We prescribe carbohydrate loading drinks in addition to free clear fluids to the point of sending for theatre. Highly protocolised anaesthetic and analgesic regimes are crucial. Patients are premedicated with long acting analgesia, and are given no or very minimal sedation to encourage early diet and ambulation. Our anaesthetic is a short acting spinal anaesthetic, with minimal haemodynamic disturbance, careful attention to fluid balance and blood loss, with replacement through cell salvage where possible, and high volume local anaesthetic infiltration by the surgeon to all cut surfaces. Importantly, surgical techniques must be consistent and remain unchanged from standard practice. Surgical approach didn’t appear to have any affect on the rate of discharge, or the time spent in hospital, but anterolateral approach patients reported slightly higher postoperative pain scores.

We initially used Pregabalin as part of our day case pain protocol as this aligned with our inpatient practice. However, we noted an excess of reported dizziness in the inpatient cohort so withdrew the usage of it from both protocols in December 2018. We have found there to be no additional benefit from the drug and indeed there has been no detrimental effect on pain scores since its withdrawal. During this study we also redefined our post-operative chemical thromboprophylaxis to include Day 1 & 2 postoperative Dalteparin doses as discharge medications to be subsequently followed by 28 days of 150mg Aspirin daily.

As an organisation, day case arthroplasty is very attractive. We have conducted a brief health economics analysis of our results. An overnight stay in our hospital costs £288. Our current average length of stay for low risk patients is 3 days. The day case pathway incurs an extra two orthopaedic outreach visits (which cost £25 per visit), representing a post operative care saving of £814 per patient.

Our initial inclusion criteria were quite strict. These widened as our confidence in the pathway grew, to include older, more unfit, larger patients requiring technically more demanding surgery. It appeared that expectation setting, patient engagement, motivation and belief in the process were perhaps more important factors than BMI and ASA grade in predicting discharge and outcome.

We have analysed the THA patients on our waiting list and anticipate that approximately 20% patients would be suitable for a day case procedure. Our hospital carries out around 300 THAs a year. If 20% of these patients were to undergo day case procedures this would improve waiting times by reducing cancellations due to lack of inpatient capacity, and make a potential saving of £48,840.

We are looking at ways of working to incorporate an overnight stay option for patients who for organisational reasons cannot go first on the list but would otherwise be suitable for day case and may be discharged early on day 1 postoperatively. One of the barriers to discharge identified was the availability of staff (our physiotherapists finish their day at 1600hrs) to mobilise patients, therefore this could be addressed by up-skilling other staff and we are currently evaluating a competency package to enable our day surgery team to undertake aspects of this role.

We have applied the learning points from this pilot to optimise our inpatient and planned trauma pathways, utilising the day case THA anaesthetic/analgesia protocol for all hip and knee patients. The ‘day case effect’ has also brought about a culture change within the unit, by demonstrating the benefits, feasibility and safety of short stay treatment both to staff and patients, we have improved length of stay and outcomes for all elective and trauma patients.

There are limitations to this study. This is a small pilot study in a highly selected group of patients, who do not represent the majority of the patients on our waiting list. We have a multi-morbid elderly population, and a wide, rural, geographical catchment, which means that for many patients a day case arthroplasty procedure is not suitable. However, based on the initial success of the pilot we are now widening the inclusion criteria for day case THA and developing a day case pathway for Total Knee Arthroplasty patients.

Conclusion

It is safe, feasible and acceptable to patients to offer total hip arthroplasty as a day case. This satisfies all the aspirations of an enhanced recovery programme and has the potential to improve outcomes for all orthopaedic patients in our institution. Expectation setting, patient education and adherence to a robust protocol were key factors.

References

- The Telegraph 2017. NHS Hospitals ordered to cancel all routine operations in January as flu spike and bed shortages lead to A&E crisis. Available from: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2018/01/02/nhs-hospitals-ordered-cancel-routine-operations-january/

- Soffin EM, YaDeau JT. Enhanced recovery after surgery for primary hip and knee arthroplasty: a review of the evidence. BJA 2016;117:iii62-72

- Zhou S, Qian W, Jiang C, Ye C, Chen X. Enhanced recovery after surgery for hip and knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Postgrad Med J 2017;93:736-42

- Wainwright TW, Gill M, McDonald DA, Middleton RG, Reed M, Sahota O, Yates P, Ljungqvist O. Consensus statement for perioperative care in total hip replacement and total knee replacement surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society recommendations. Acta Orthop. 2020 Feb;91(1):3-19.

- Kehlet H. Multimodal approach to control postoperative pathophysiology and rehabilitation. BJA 1997;78(5):606-17

- Larsen JR, Skovgaard B, Pryno T, Bendikas L, Mikkelsen LR, Laursen M et al. Feasibility of day-case total hip arthoplasty: a single-centre observational study. Hip Int 2017;27(1): 60-5

- Brerend JR, Lombardi AV Jr, Brerend ME, Adams JB, Morris MJ. The outpatient total hip arthroplasty: a paradigm change. Bone Joint J 2018;100-B:31-5

- Pollock M, Somerville L, Firth A, Lanting B. Outpatient total hip arthroplasty, total knee arthroplasty and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: a systematic review of the literature. JBJS Rev 2016;4:12

- Li J, Rubin LE, Mariano ER. Essential elements of an outpatient total joint replacement programme. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2019 Oct;32(5):643-648.

- Sershon RA, McDonald JF 3rd, Ho H, Goyal N, Hamilton WG. Outpatient Total Hip Arthroplasty Performed at an Ambulatory Surgery Center vs Hospital Outpatient Setting: Complications, Revisions, and Readmissions. J Arthroplasty. 2019 Dec;34(12):2861-2865.

- Husted C, Gromov K, Hansen HK, Troelsen A, Kristensen BB, Husted H. Outpatient total hip or knee arthroplasty in ambulatory surgery center versus arthroplasty ward: a randomized controlled trial. Acta Orthop. 2020 Feb;91(1):42-47.

- Lazic S, Broughton O, Kellet CF, Kader DF, Villet L, Rivière C. Day case surgery for total hip and knee replacement. EFORT Open Rev 2018;3(4). Doi:

- Bradley B, Griffith S, Stocker M, Hockings M, Isaac D. Unicompartmental Knee Replacement as Day Case Surgery: A Pilot Study. The Journal of One Day Surgery 2014;24:16–18

- Bradley B, Middleton S, Davis N, Williams M, Stocker M, Isaac DL. Discharge on the day of surgery following unicompartmental knee arthroplasty within the United Kingdom NHS. Bone Joint J 2017;99-B(6):788-92

- Churchill L, Pollock M, Lebedeva Y, Pasic N, Bryant D, Howard J, Lanting B, Laliberte Rudman D. Optimizing outpatient total hip arthroplasty: perspectives of key stakeholders. Can J Surg. 2018 Dec 1;61(6):370-376.

- British Association of Day Surgery. Directory of Procedures 6th Edition. London.

- Manassero A, Fanelli A. Prilocaine hydrochloride 2% hyperbaric solution for intrathecal injection: a clinical review. Loc Reg Anesth 2017;10:15-24

- Amundson AW1, Panchamia JK, Jacob AK. Anesthesia for Same-Day Total Joint Replacement. Anesthesiol Clin. 2019 Jun;37(2):251-264

Cite this article as https://daysurgeryuk.net/en/resources/journal-of-one-day-surgery/?u=/2020-journal/jods-304-november-2020/introduction-of-day-case-pathway-for-total-hip-arthroplasty/

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/43853/304-kent.pdf