Improving informed consent for laparoscopic cholecystectomy using audio visual aids: A quality improvement project « Contents

Mehdi S. N. Raza Consultant Surgeon¹

Sagar Gurung resident surgical officer, Queen Mary’s Hospital, Sidcup

Himalaya Gurung resident surgical officer, Queen Mary’s Hospital, Sidcup

Department of Surgery, Dartford and Gravesham NHS trust, Kent

Corresponding Author: Mr. Mehdi S. N. Raza Surgical Directorate, Darenth Wood Rd, Dartford DA2 8DA Email: mehdiraza@nhs.net

Source of funding: author for video/audit department

Keywords: Informed consent, Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, Audio-visual aids

Abstract

Background: The current time requires clinicians to improve the health education we provide in clinics. Individuals undergoing major surgery should be well informed and provided with enough time to make a decision.

Methods: This is a closed loop audit aimed at improving the informed consent process for day case laparoscopic cholecystectomy by audio-visual aids in clinics. We asked fifty patients attending clinics for consideration for a day case laparoscopic cholecystectomy what they thought of the standard informed consent by filling a simple questionnaire after a clinic visit. After reviewing the results, we realised the process of consenting needs to improve. We then improved the informed consent procedure by adding an informative video for clinics and developed a new information leaflet. Thirty-five patients gave their feedback on the new consenting process by filling in a simple questionnaire at the end of their clinic consultation.

Results: A survey assessed our current consenting process. Out of the 50 returned questionnaires returned, thirteen patients did not remember any of the conversation in clinic. Five patients were consented on the day of the surgery. In conclusion, individuals agreed audio-visual information would be beneficial for the consenting procedure in clinic.

We organised a four-minute animated video and a new information leaflet to improve our informed consent procedure. Information included was about the perioperative journey and specific anatomy and risks of a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. We received excellent feedback from 35 patients. We have applied this change to the current day case practice.

Conclusion: Audio-visual aids help in providing patients with good quality information for a well-informed mutual agreement about major surgical procedures. The author finds audio visual aids are useful for discussing major surgical procedures in the clinic and does not affect the amount of time spent with each patient.

Introduction

Gallbladder surgery has evolved through a series of interesting events over more than a century. After the first ever-recorded cholecystectomy performed in 1882, little did we know that it would become one of the most performed operations worldwide? The only procedures performed prior to this were drainage of abscesses, removal of stones or management of cholecystic fistulas.(Sparkman 1982)

It was 103 years later that the first laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed by Professor Dr Med Erich Mühe of Böblingen, Germany on September 12, 1985. He eventually received recognition of his work in 1995 with The German Surgical Society Anniversary Award. He can be given credit for inventing numerous instruments used in a laparoscopic cholecystectomy.(Reynolds 2001)

Despite technological advancements throughout the last 3 decades, the procedure has not changed much from the one performed by Professor Muhe in 1985. Some trusts are performing more of these procedures as ‘one stop’ care in day-case centres, by setting up pathways and streamlining the referral and gallbladder imaging process. Despite it being one of the commonest day case procedures, patients often are referred from clinicians with limited surgical experience of the procedure. This is where audio-visual education in clinics can be beneficial. (Clarke et al. 2011)

Our initial audit was a survey of the current process of informed consent for a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. We made improvements in consenting with audio-visual aids in the form of a video, literature and signing a written consent in clinic. It is common knowledge that more audio-visual aids improve health education and understanding shown in randomised controlled trials discussed below. We found numerous weaknesses in the quality of information they provided and decided to produce our own information video. We will provide the link of the consent video to access through the hospital website for the benefit of patients and clinicians.

Methods and Patients

Surgeons performing a laparoscopic cholecystectomy may only see the patients on the day of the procedure due to numerous reasons. This is despite our trust guidelines requiring us to consent patients in clinic. Informed consent is the mutual agreement between the clinician and the individual for a surgical procedure after thorough discussion of the options, the risks and the perioperative pathway of surgery. We know that despite thousands of such day case procedures progress uneventfully, complications still happen. A thorough and high-quality consenting process discussing general and specific gallbladder surgery risks is essential.

We discussed the audit proposal within our audit department on the 29th of June 2017 and produced a scope document and a simple questionnaire.

The individuals included in the survey were booked from across both hospital sites. No emergency cases were included for this audit. The initial survey over three months took place in Queen Mary’s Hospital (one of our two sites) for ease of completion of surveys. We asked individuals specific questions on components of the informed consent of a laparoscopic cholecystectomy like need for illustrative basic anatomy and more visual information of risks of surgery. The National Institute of Clinic Excellence (NICE) guidelines outline the best medical practice for informed consent. We reviewed the patient information leaflets in our trust and compared them with local hospital trusts. We received 50 questionnaires filled in after standard consultation for a laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Results

The results revealed that all the patients were informed of the options, risks and benefits of the procedure at clinic appointment. Patients were provided information leaflets in the clinic. 32 patients in the clinic out of the 50 received a copy of the signed consent form.

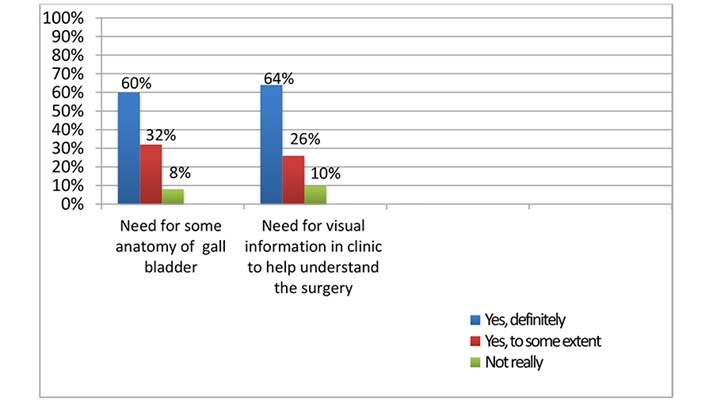

Thirteen patients did not remember the conversation in the clinic. Five patients were consented on the day of surgery. Most individuals agreed strongly that audiovisual aids would help in understanding the anatomy and the complex hepatobiliary risks from a laparoscopic cholecystectomy, see Graph 1.

Graph 1: survey of patients attending clinic for consideration of surgery.

We presented the survey results in our monthly audit meeting and started working on a short-informed consent video for clinics. The aim was to provide improved literature and a copy of the signed consent form to the patient.

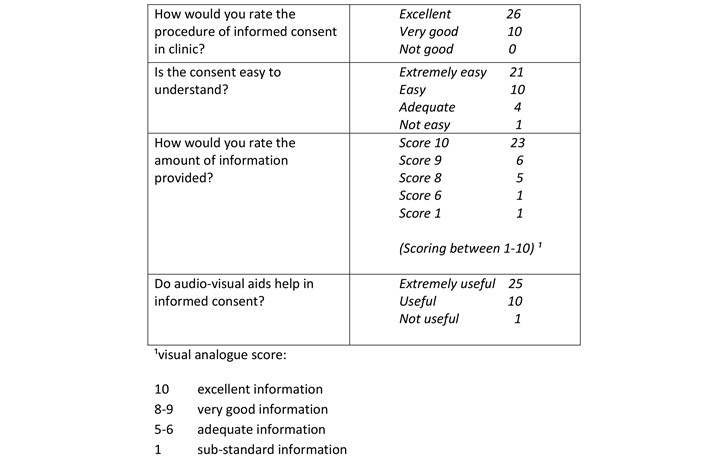

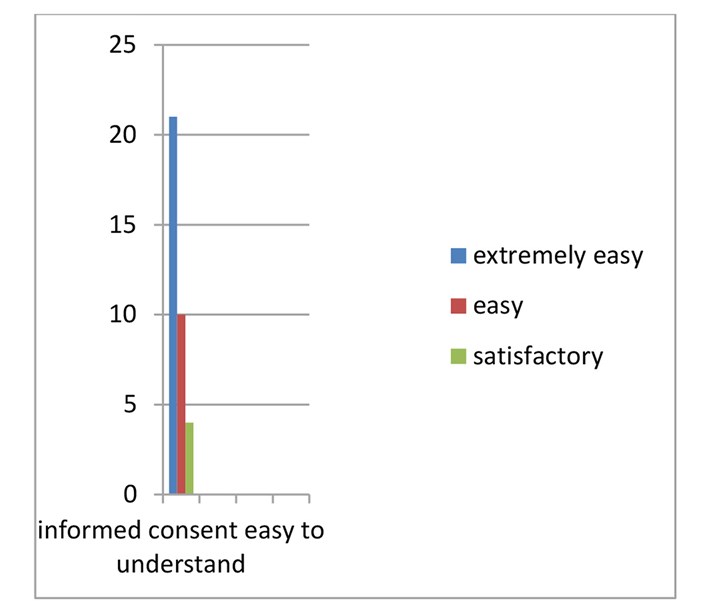

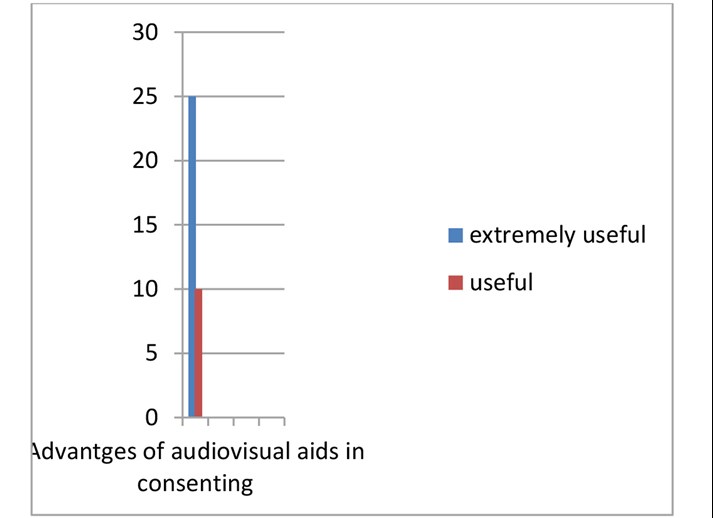

Work on the video involved making sure that not only all the relevant information is provided but is easily understandable. Animations rather than real time images by a trained audio-visual engineer provided comfortable viewing and avoided distressing patients. Our clinic consultation involved the standard informed consent procedure and display of the consent video. We provided the patients with a copy of the consent and literature to take home. We asked Individuals to fill the second survey after this process in clinic. We received excellent feedback from the 35 patients surveyed, see Table 1 and Graphs 2-4.

Table 1: Results of second questionnaire.

Graph 2: assessment of informed consent process.

Graph 3: Is the informed consent easy to understand?

Graph 4: Are audio-visual aids advantageous in consenting.

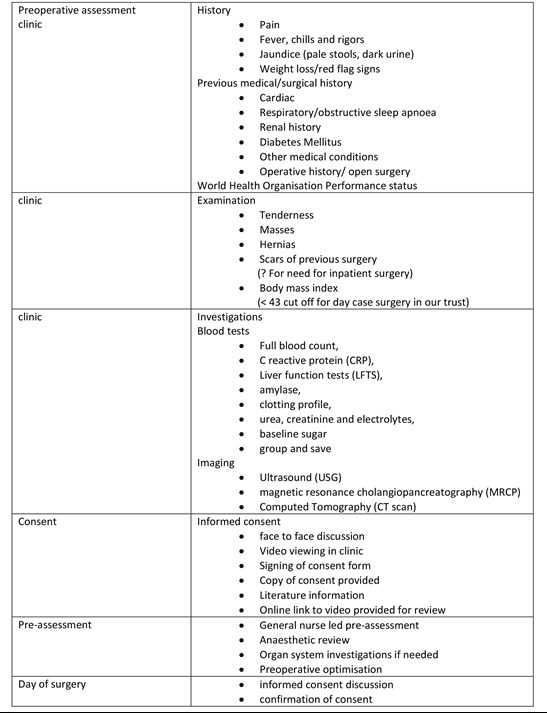

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy pathway.

Discussion

The current health system is undergoing gradual and constant reform. Though patient autonomy is paramount in the process of informed consent, this was not the case just 50 years ago. Until only 50 years ago, a paternalistic physician approach was preferred over the concerns of the patients. Even the Hippocratic writings of the fourth and fifth century BC provide an extremely disappointing history in the context of informed consent. The GMC guidance emphasises that you should, ‘share information in a way the patient can understand and, wherever possible, in a place and at a time when they are best able to understand and retain it’ (GMC 2008).

Due to the nature of service provisions in the National Health Service (NHS), the operating surgeon does not always encounter the same patient in clinic. Time constraints can sometimes even mean that individuals are consented on the day of the surgery. This is despite our hospital trust guidelines to consent individuals undergoing major procedures in clinics weeks prior to the surgery date. Unfortunately, it is practically impossible for specialists to see all the patients personally in certain high-volume cases like gallbladder and hernia surgery. The aim of our closed loop audit was to find the problems in our perioperative patient’s journey related to informed consent and to try to improve the information provided.

Elements of an informed consent form:

An effective and ethically valid informed consent needs to consider preconditions like competence on part of the patient to understand and make a decision and the voluntariness in deciding, free from controlling influence, including coercion, persuasion or manipulation.

The elements essential for information provided should include not only thorough disclosure of material information to the patient, including the alternatives, risks & benefits of treatment but also the physician’s recommendation of a plan.

The consent elements should include the decision in favour of a plan by the patient and authorization given by the patient of the chosen plan. (Beauchamp 2011)

Health education and its retention can improve with numerous techniques like literature about the procedure, ’repeat back’ to assess retention of knowledge, second clinic discussion and audio-visual aids.

Repeating the information provided in any form can be useful to make an informed decision. In a multicentre randomised controlled trial (RCT), individuals in the control group were consented the standard way and the experimental group assessed with ‘repeat back’ including standard informed consent. It was concluded after 575 patients assessed by a questionnaire that individuals benefitting from repeat back took longer to consent but had much improved comprehension of the procedure.(Fink et al. 2010)

Another smaller sized randomised control trial showed a simplified standard informed consent by highlighting text in bullet points and graphical illustrations improved health education in individuals undergoing surgery.

Thirty-seven individuals were consented in the standard way whereas 33 individuals had a graphically formatted, easy to understand consent form. Assessment questionnaires were filled in by the individuals showing improved comprehension of the surgical procedure and the risks.(Borello et al. 2016)

The use of multimedia including video and graphic illustrations aid in improving health education and the tools can repeated in the comfort of the individual’s own living room to reinforce the already acquired knowledge. We have prepared an animated video that provided information relating to the overall perioperative process in the setting of a typical district NHS hospital.

The video can be seen by clicking here.

The video can be seen by clicking here.

There are randomised control trials that used multimedia to improve the standard of the informed consent process. In a German RCT, 76 individuals were shown real-time as well as animated video of a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. This video was prepared over a 3-year period with the collaboration of surgeons, psychologists and linguists that defined the major relevant topics. At the end of the consent with audio-visual aids and standard informed consent, thirty-five individuals were asked to fill in a questionnaire. Forty-one individuals were consented in the standard way. It concluded that audio-visual aids improved the perceived understanding of risks of surgery especially in those with less formal education. The drawback of the study was a small sample size. (Bollschweiler et al. 2009)

In a larger RCT from Germany, preoperative patient education using a multimedia digital versatile disc (DVD) improved the informed consent in patients undergoing a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The University of Munich, Germany produced the DVD. One hundred and fourteen patients in the experiment group saw the DVD and underwent standard informed consent compared to 98 patients having a standard informed consent. It was 25 minutes long and involved a real time surgeon-patient interaction as well as animations. They came to the conclusion that individuals fluent in German language and were of a younger age benefitted the most due to better education and retention of health education. (Wilhelm et al. 2009)

There have been similar studies using multimedia facilities to improve the quality and amount of retention of health education for certain surgical procedures with very encouraging outcomes on standard questionnaires and scoring systems. However, in one study on individuals having cataract surgery, the retention of information decreased as age of the individuals increased. Age and mental ability needs to be taken into account while providing procedure information. (Tipotsch-Maca et al. 2016)

Contents of the informed consent need to include the most common and the most serious of complications, however consensus between even groups of surgeons can be difficult to attain because of a variety individual opinion and experience. There have been attempts to bridge this difficulty by applying techniques like the Modified Delphi Technique to achieve consensus and to optimise the information provided. A study used the above technique to deliver an informed consent video in individuals requiring debridement for limb trauma. A panel of experts including experienced patients decided on the final information to be included in the video. They used a ’final knowledge measure ‘questionnaire. The advantage was acquiring the consensus from all the experienced stakeholders including patients to build on the essential information provided to the patient. (Lin et al. 2017)

Despite our efforts to improve the process, we do acknowledge some weaknesses. Firstly, not all risks can be discussed in a short video and there are bound to be some risks (though uncommon) not included in the video. Secondly, some terms used in the video might be too technical for someone not from a healthcare background but had to be included to keep the video short.

The author believes that it takes about 3- 4 minutes to fill in the consent form and print out the literature while patients see the video. Once the video concludes and the consent form is ready, a thorough discussion takes place prior to formally signing the consent. The repetition assists in educating the individual thoroughly.

Conclusion

Informed consent is an opportunity to discuss the clinical management between the clinician and the individual undergoing an intervention rather than an exercise to fulfil legal requirements. To maintain this sacred bond between the patient and clinician, an informed consent that provides adequate knowledge and meaningful understanding should be of utmost priority. Multimedia can be utilised to improve this process.

References

- Sparkman RS. 1982. 100th Anniversary of the First Cholecystectomy: A Reprinting of the 50th Anniversary Article From the Archives of Surgery, July 1932. Arch Surg. doi:10.1001/archsurg.1982.01380360001001.

- Reynolds W. 2001. The First Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. J Soc Laparoendosc Surg.

- Clarke MG, Wheatley T, Hill M, Werrett G, Sanders G. 2011. An Effective Approach to Improving Day-Case Rates following Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. Minim Invasive Surg. doi:10.1155/2011/564587.

- Beauchamp TL. 2011. Informed consent: Its history, meaning, and present challenges. Cambridge Q Healthc Ethics. doi:10.1017/S0963180111000259.

- Fink AS, Prochazka A V., Henderson WG, Bartenfeld D, Nyirenda C, Webb A, Berger DH, Itani K, Whitehill T, Edwards J, et al. 2010. Enhancement of surgical informed consent by addition of repeat back: A multicenter, randomized controlled clinical trial. Ann Surg. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181e3ec61.

- Borello A, Ferrarese A, Passera R, Surace A, Marola S, Buccelli C, Niola M, Di Lorenzo P, Amato M, Di Domenico L, et al. 2016. Use of a simplified consent form to facilitate patient understanding of informed consent for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Open Med. doi:10.1515/med-2016-0092.

- Bollschweiler E, Hölscher AH, Obliers R. 2009. Improving Informed Consent of Surgical Patients Using a Multimedia-Based Program? Ann Surg. doi:10.1097/sla.0b013e31819ac459.

- Wilhelm D, Gillen S, Wirnhier H, Kranzfelder M, Schneider A, Schmidt A, Friess H, Feussner H. 2009. Extended preoperative patient education using a multimedia DVD-impact on patients receiving a laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A randomised controlled trial. Langenbeck’s Arch Surg. doi:10.1007/s00423-008-0460-x.

- Tipotsch-Maca SM, Varsits RM, Ginzel C, Vecsei-Marlovits P V. 2016. Effect of a multimedia-assisted informed consent procedure on the information gain, satisfaction, and anxiety of cataract surgery patients. J Cataract Refract Surg. doi:10.1016/j.jcrs.2015.08.019.

- Lin YK, Chen CW, Lee WC, Lin TY, Kuo LC, Lin CJ, Shi L, Tien YC, Cheng YC. 2017. Development and pilot testing of an informed consent video for patients with limb trauma prior to debridement surgery using a modified Delphi technique. BMC Med Ethics. doi:10.1186/s12910-017-0228-3.

(Click on image to go to the company website.)

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/34940/301-raza.pdf