Audit of the Recording Of Hba1c and Blood Pressure in Elective Surgical Referrals From Primary Care « Contents

Joseph Pease, Nazrul Islam, Thazin Wynn & Anna Lipp

Norfolk and Norwich University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

Corresponding author: Dr Joseph Pease, Academic FY2 doctor at Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital

Email: joseph.pease@nnuh.nhs.uk

Key words: diabetes, hypertension, referral, elective surgery

Abstract

Objectives: Updated guidelines for the peri-operative management of patients with diabetes and hypertension were recently published, and suggest primary care referrals to surgery should include information regarding patients’ diabetic control (glycated haemoglobin - HbA1c) and blood pressure. This allows optimisation of glycaemic control and blood pressure before surgery to reduce the risk of complications, prolonged hospital stay and procedure cancellation; which impacts the patient’s physical and mental health, and has significant financial implications. This audit aims to assess whether surgical referrals from primary care are including this information, and to identify if certain referral formats include them more consistently.

Method: Data including diabetic status, glycated haemoglobin and blood pressure readings were collected from routine referrals between January-February 2017; encompassing 200 adult patients from breast, urology, general and vascular surgery. The number of referrals including this information was calculated, as well as whether they were within guideline limits. Results: 185 referrals contained information on comorbidities, of which 19 patients had diabetes, 3 of whom had accompanying HbA1c levels. Of the 57 patients with hypertension: 49 referrals included a blood pressure measurement, with 6 patients above the advised range.

Conclusions: Few referral letters provided sufficient information recommended by guidelines. Better reporting of HbA1c levels is necessary. Blood pressure, body mass index and smoking status was reported more often, however not consistently. Referrals with electronic summaries were most likely to contain the necessary information. A standardised proforma for elective referrals may be useful in ensuring that relevant information is included. It may be the case that the new guidelines are not yet fully integrated within primary care.

Introduction

In an increasingly burdened National Health Service (NHS), it is essential that things go right first time, with as few interruptions or complications as possible. Referrals for elective surgical procedures from primary care providers should contain sufficient information to initiate the decision-making process for surgeons and anaesthetists for how suitable a patient is for an operation. Guidelines exist with recommendations for optimisation of the patient’s health prior to routine surgery, particularly with regard to glycaemic control and blood pressure (BP). Referral letters are therefore pivotal in influencing the management of surgical patients, yet there is considerable variability in format and content. Including the recommended information may trigger a chain of events, which may ultimately help to reduce the risk of complications, mortality, prolonged hospital stay or postponed procedures. This has wide implications affecting both the patient and the NHS. This audit aimed to identify how many primary care referrals for routine operations included the recommended information about two important perioperative considerations – glycaemic control and BP. It also aimed to identify any effective proformas or referral formats that consistently include this information.

10-15% of patients undergoing surgery have diabetes, and these patients are at greater risk of complications, mortality and extended hospital admission.1 It is therefore imperative that glycaemic control is optimised prior to elective surgery, ideally before referral. Updated guidelines for the perioperative management of patients with diabetes were published in 2015, stating that primary care referrals should contain information about the duration, type of diabetes, current treatment and complications. Additionally, the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommend that referrals should contain the patient’s most recent HbA1c, and that all patients with diabetes should be offered HbA1c testing if they have not been tested within the past 3 months.2 Glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) is widely used as a marker of glycaemic control. Elevated HbA1c levels has been found to be associated with an increased rate of mortality in cardiac surgical patients, and is also with a greater risk of complications and infections.4,5 Since 2012, guidelines have suggested that elective procedures should be postponed if the patient’s HbA1c is ≥69mmol/mol to minimise the risk of these adverse events.3 With these guidelines in mind, primary care referral letters for elective procedures provide key indicators about diabetic control and have the potential to improve glycaemic control at an earlier and more convenient stage for both the patient and the perioperative team.

Hypertension has been shown to be the most common medical cause for postponing surgery.6,7 It is recognised as a significant risk factor in the development of cardiovascular disease and also poses difficulties for the anaesthetist during the perioperative period.7 Patients referred for elective surgery with a BP measurement ≥160/100mmHg in primary care should have their operation postponed until it has been reduced.7

There is no standardised way of referring patients for elective surgical procedures from primary care. A variety of referral formats are used, and are often a combination of letters and a summary of the patient’s healthcare record. However, the content of referral letters is largely down to the individual clinician’s discretion, which varies between clinicians and practices.

Audit Objectives

- To determine whether primary care referral letters contain sufficient information about diabetic control, BP and other clinical information relevant for elective operations

- To examine which referral formats consistently include sufficient information about relative aspects of a patients medical history

Assessing the strengths and weaknesses of the current referral systems allows for identification of ways to improve and streamline the elective surgery pathway for patients, maximising the opportunity for day surgery and hopefully reducing the risk of complications.

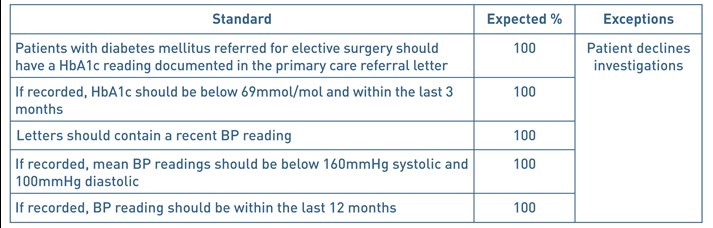

The following standards were therefore devised:

Table 1. Audit standards

Methods

Inclusion criteria: referrals for adult patients (aged 18 years and above) from primary care to urology, general, breast or vascular surgery under a ‘routine’ referral pathway July 2016 to March 2017.

Exclusion Criteria: patients referred under ‘2 week wait’ or ‘urgent’ referral pathways. Patients aged under 18 years old. Patients referred and subsequently redirected to a non-surgical specialty.

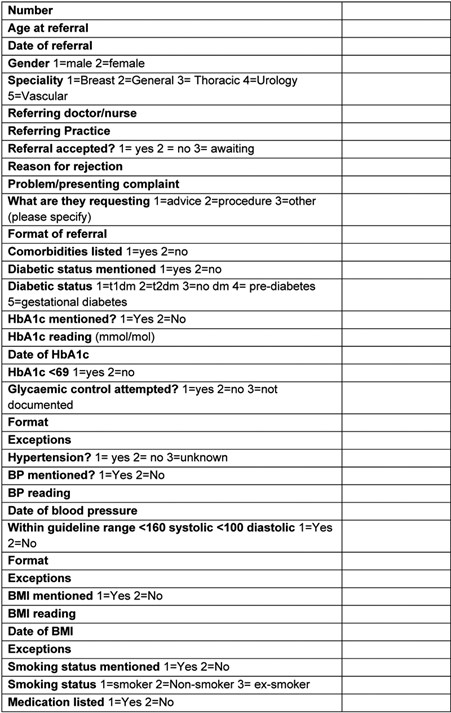

Referrals arranged in descending chronological order were accessed using an electronic Outpatient Referral system. The 50 most recent routine referrals were accessed for each of the following surgical specialties: general surgery, urology, breast surgery and vascular surgery. Anonymised data was recorded onto a data collection sheet on Microsoft Excel (see appendix 1) on a password-protected computer.

Article continues after ad.

Results

Information from 200 referrals was obtained, consisting of 112 women and 88 men, ranging from 18 to 96 years old. No exceptions were found. 148 of the 200 referrals were requesting advice on further management or a review of the patient and 44 referrals were directly requesting a procedure or operation. 8 referrals were either requesting both advice and a procedure, or were concerning other matters.

19 patients were stated as having diabetes within the referral letter or accompanying electronic summary. 18 of these had type 2 diabetes and one patient had type 1. 5 patients had ‘prediabetes’. 161 patients were presumed to be non-diabetic as there was no diagnosis of diabetes listed and there was insufficient clinical information to determine if the remaining 15 patients were diabetic or not. Of the 19 referrals of patients with diabetes, 3 (15.8%) of these included a HbA1c reading. 5 non-diabetic patient referrals also had an accompanying HbA1c reading. All 8 of these readings were below 69mmol/mol. 2 were taken within 3 months. 1 HbA1c reading was recorded 3 months and 1 day before the date of referral.

57 patients had a diagnosis of hypertension that was apparent within the referral letter. 132 patients had no listed diagnosis of hypertension and it was unclear whether the remaining 11 patients had hypertension or not.

Just under half of all referrals (96/200) included a BP measurement. Of these, 90 patients had a BP reading less than 160/100mmHg. 8 patients had a BP reading ≥160/100mmHg, 6 of these were known to have hypertension. For patients with known hypertension, 49 of 57 (86%) referrals included a BP reading. 69/96 (72%) readings were taken within the last 12 months. 23 were older than 12 months, and 4 were not clearly dated.

The most widely used referral format was a letter with an accompanying patient healthcare summary, with 79 of the 200 referrals being made this way. The second most commonly used format was a letter alone, either electronic or printed, which comprised 51 referrals. All 50 breast referrals were made using a local, standardised breast care proforma. The majority of these also included a healthcare summary (37/50). Each format was reviewed to see if it contained both a BP measurement and a HbA1c reading (if appropriate). The referral format that most consistently included both of these values was a letter with an attached healthcare summary (58.23%). The addition of an electronic healthcare summary to a referral letter resulted in almost double the percentage of referrals including the necessary information (29.41% vs 58.23%).

Figure 1. Proportion of referrals containing a BP measurement and a HbA1c value (if appropriate) by format.

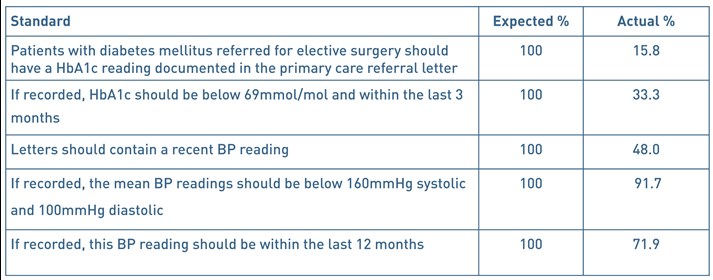

Table 2. Audit Standards and results – summary.

Discussion

19 of the 200 patients had diabetes, which roughly reflects the proportion of surgical patients with diabetes. HbA1c readings were not regularly included in referrals for these patients. This finding impacts the care pathway of this patient as it should be measured prior to pre-operative assessment. This may incur delays for the patient if it is found to be above 69mmol/mol, and could result in inefficient use of resources and clinic time due to an inappropriate referral. Alternatively, if the operation goes ahead, it would be subjecting the patient to risks associated with suboptimal glycaemic control. Whilst it is likely that HbA1c monitoring is taking place, either in primary or secondary care, such information may not be readily available.

96 of the 200 referrals (48%) contained a BP reading. However, if the patient was known to have hypertension, then the proportion of referrals containing a BP reading was 86%, showing that general practitioners (GPs) recognise the perioperative importance of including a BP reading when referring the patient if it is known to be high. Of the 148 patients referred for advice/review only, 68 (45.95%) of these referrals included a BP reading. When compared to the 44 patients referred specifically for a procedure, 25 (56.82%) included a BP reading. This may suggest that GPs are more vigilant with blood pressure documentation when they know that the patient is more likely to have an operation.

This audit has demonstrated the variety of referral formats that are used by primary care. With the exception of breast services, there is currently no set proforma for referring patients to a surgical specialty. The format that most reliably included the necessary information was a letter with attached healthcare summary, but there were still many referrals using this format that did not include information about blood pressure or HbA1c. Including a healthcare summary of the patient within the referral did improve the rates of documented BP measurements and other important factors, so it is worth appreciating the benefits of attaching these summaries. Whilst most aspects of a patient’s healthcare record can be obtained by secondary care, this is an avoidable use of time and resources. There was a relatively small number of patients with diabetes used in this audit as there was no practical way of identifying only diabetic patients using the software available. Perhaps an audit exclusively assessing patients with diabetes would be more useful.

Not all patients referred to secondary care by GPs were for a definitive surgical procedure, with the majority of patients being referred for review or advice. Whilst it is unknown whether these patients ultimately had an operation, it might still influence the content of the referral letter if the GP believes that the patient will be undergoing an operation. This issue could be addressed in future audits by only selecting referrals where a specific operation is requested. However, being able to compare the content of referrals requesting advice in contrast to those requesting a specific procedure is useful.

The variability in content and format of surgical referral letters highlights the problem that recommended information can be missed. Although further studies are needed to fully elucidate the impact of not including such information, for example, rates of postponed operations or unplanned admission after day surgery, it is a logical step to find ways to ensure that all referrals contain the necessary data. Additionally, this audit suggests that more work is needed to ensure that perioperative guidelines are better integrated into primary care. A follow-up survey of primary care providers would be useful to ascertain the awareness of these.

Elective surgical referrals may also provide a chance to opportunistically motivate and educate patients on managing their health, with the shared goal of undergoing a procedure as safely as possible. It could provide an indication of the ongoing management of chronic conditions such as diabetes and hypertension. Therefore, the benefits of a well-completed referral letter are not limited to the anaesthetist, but are advantageous to the GP and patient as well.

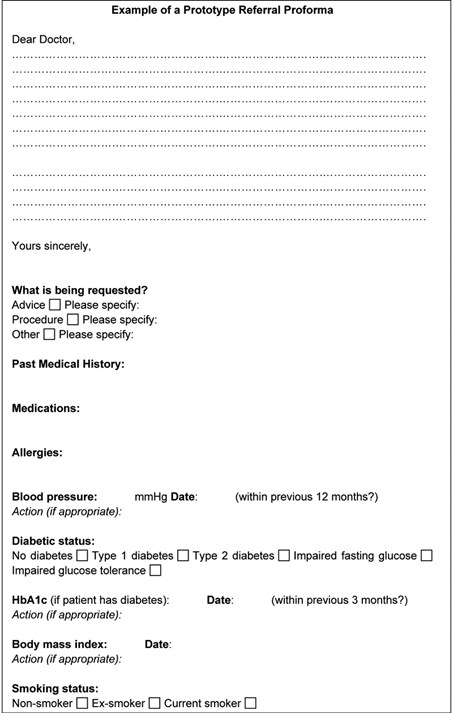

We suggest the referral process could be improved by implementing an electronic proforma, to ensure that these key clinical variables are included (example in appendix 1). Alternatively, this could be incorporated into the primary care software systems as a prompt or automated message when beginning to write a referral with a checklist of key questions pertinent to each of the patient’s conditions.

Ultimately, including the appropriate information in every referral letter is a relatively quick and simple process, and could help improve the standard of care provided to patients.

Acknowledgements

Tahlia Collins – audit facilitator

Declaration of Interests

None declared from any of the authors

References

- Barker P, Creasy PE, Dhatariya K, Levy N, Lipp A. Peri-operative management of the surgical patient with diabetes. Anaesthesia 2015. doi:10.1111/anae.13233

- National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (2016). Preoperative tests (update) – Routine preoperative tests for elective surgery. NICE Guideline (NG45).

- Dhatariya K et al. NHS Diabetes guideline for the perioperative management of the adult patient with diabetes. Diabet Med. 2012 Apr;29(4):420-33. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03582.x.

- Aldam P, Levy N, Hall GM. Perioperative management of diabetic patients: new controversies. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2014; 113(6):906-909. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aeu259

- Sato H, Carvalho G, Sato T, Lattermann R, Matsukawa T, Schricker T. The Association of Preoperative Glycemic Control, Intraoperative Insulin Sensitivity, and Outcomes after Cardiac Surgery. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2010; 95(9): 4338-4344.

- Dix P, Howell S. Survey of cancellation rate of hypertensive patients undergoing anaesthesia and elective surgery. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2001; 86(6):789-793.

- Hartle A et al. The measurement of adult blood pressure and management of hypertension before elective surgery. Anaesthesia 2016; 71:326-337. doi:10.1111/anae.13348

Figure 2. Questions from the data collection sheet

Example of a prototype referral proforma.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/26188/292-pease.pdf